More than 15 years after creating JavaScript, Brendan Eich conceded that JS had

The regret is sincere. I’ll never be a fan of JavaScript. But Brendan Eich achieved something authentically great with Mozilla. In 1998, while still a Netscape employee, he helped start the Mozilla project. Starting in 2003, he worked at Mozilla for 11 years, shipping influential software, especially the Firefox web browser. But more than that, a core part of Mozilla’s identity has always been its excellent ethics around open source and web citizenship. That would’ve been a terrific legacy for any software engineer.

Apparently, however, Mr. Eich has undergone some kind of late-career conversion to the dark side of the force. With Brave, Mr. Eich wants to ruin my work—and that of every other creator who’s still propping up what’s left of the ad-free internet—so that he (and his venture investors) may profit. How? By layering ads over my ad-free website, while convincing web users that they’re part of some virtuous new economy.

Sorry Mr. Eich, but I refuse to cooperate. As soon as I figure out how to detect the Brave web browser by technological means—a task you’re deliberately making difficult, because you know that many publishers would like to do the same—I will make sure that every Brave visitor gets this as their landing page.

Because they deserve to know that Brave is bullshit.

For web users, Brave is a company, founded by Mr. Eich, that makes an eponymous web browser. According to Brave, its browser offers two key benefits:

The

“speed, security, and privacy” that comes from automatically blocking ads and trackers.The virtuous pleasure of giving

“publishers back their fair share of Internet revenue.”

Before we go further, let’s notice that Brave’s pitch blatantly sidesteps the fact that web publishers already have a preferred way of getting their

Hey, I don’t like those ads either. Though I’m skeptical that blocking them does much good in the aggregate.

It’s definitely true, however, that blocking them makes web browsing faster. Although every web browser supports ad blocking (usually through external plug-ins), Brave is the first to declare total war on the ad economy of the web.

Well—sort of. Brave the browser, like every other web browser, is free to end users. But because Brave the company, like every other tech company, has bills to pay, and investors to enrich, it needs a revenue model. And that model is—prepare to unholster your complete lack of surprise—ads.

But wait—come back! Not just any ads. New and improved ads. Ads that are

Perhaps concerned that users might detect that Brave is doing nothing more than substituting one set of ads for another, Brave has put some trendy misdirection into the trick: cryptocurrency. Brave has invented something called the

To close the circle, web creators who want their

The best I can say for Brave is that it’s clever. Not the ads per se. But the audacity of introducing a private advertising ecosystem. And roping users and creators into it with a crypto coin.

But in all other ways, it’s just as awful as the system it proposes to replace. Worse, really, because Brave takes its bad idea and layers on the usual whipped-bullshit virtue topping that tech companies deploy so we can’t quite see what’s really going on. Moreover, Brave’s timing couldn’t be better: as Big Tech’s reputation keeps taking hits, Brave can hold itself out as the contrarian option to repair the web.

As one of the creators who I guess is supposed to be grateful to Brave, I disagree. Once I scrape away the topping, it’s apparent Brave is serving up the same old shit sandwich.

About which, more below. But first, let’s rewind.

The most disappointing aspect of this story is that before Brave, Brendan Eich had an impressive track record. He’s a software engineer who’s been involved in web browsers as long as there’s been a web. Shortly after he joined web pioneer Netscape in 1995, he claims he had to create JavaScript

In 1998, Eich helped spin out Netscape’s source code into the open-source Mozilla project. In 2003, Eich left Netscape for Mozilla, serving the project in various capacities until 2014.

To give Mr. Eich his due: in the last 25 years, one could argue that Mozilla has been one of the top five citizens of the internet. They’ve always had good ethics. They’ve made a lot of really good software, most of all the Firefox web browser. They’ve led by example and held themselves accountable. And Mozilla has survived despite the commercial web often being hostile to Mozilla’s values. For whatever part of this Mr. Eich was responsible for, he deserves credit and gratitude.

I hesitate to mention what happened next, because it’s not strictly part of Mr. Eich’s technology portfolio. And yet. It does seem to play a role in Brave’s origin story, much the same way that Mr. Incredible’s (r)ejection of Incrediboy led him to become Syndrome.

In March 2014, Mr. Eich was appointed CEO of Mozilla Corporation. That’s the kind of job you don’t take unless you plan to stick around for a while. Days later, people of the internet discovered that Mr. Eich had financially supported California Proposition 8, a notorious 2008 ballot measure that wanted to ban same-sex marriage in California. Backlash followed. After offering a heartfelt non-apology, Mr. Eich resigned.

I don’t care if Mr. Eich is politically conservative. I’m not. But I don’t think he owed anyone an apology. His views were not a secret. Still, I don’t see him as a victim either. Records of political donations are public for a reason.

If anything, the board of Mozilla should’ve noticed the likelihood for controversy before they elevated him to CEO. If they had, maybe they wouldn’t have made the appointment. Or maybe they would’ve found a way to work around the PR problem. In any case, maybe Mr. Eich would’ve remained at Mozilla. The kerfuffle would’ve faded. And Mr. Eich could’ve gone back to being a rich, famous, and influential web engineer.

Instead, he left. Shortly thereafter, he started work on the company that became Brave, which ethically speaking is Mozilla’s exact antipode. I have no special insight into Mr. Eich’s motivations. But given the timing of events, it’s hard not to see Brave partly as a response to his involuntary exit from Mozilla. As a browser maker, Brave’s competition is more than just Mozilla Firefox. But Brave’s theory of the web seems almost like the Bizarro-world refraction of Mozilla’s.

For instance, in an interview at the time, Mr. Eich was concerned that as CEO, his free speech was being suppressed, and that the rush to judgment was inconsistent with Mozilla’s

In the same interview, Mr. Eich described Mozilla as

If Mr. Eich had wanted to be accurate, he would’ve called his new browser

The name Brave implies that other tech companies are shrinking from the job of improving the broken aspects of the web. Near the top of that list is what is now a decades-long failure to devise a sustainable model to fund creators and publishers.

There is truth to this critique. As I write this, Google’s Chrome browser is by far the most popular. But Google gets almost all its money from ads, and has no incentive to do any favors for publishers. Likewise Facebook, despite occasional grunting noises to the contrary.

But the idea that Brave is somehow sticking its neck out is laughable. Here’s what I find most cowardly about Brave:

Zero innovation. Brave isn’t offering a new idea. It’s just substituting one set of ads for another. It’s as if you were punching yourself in the face for days, and someone handed you a rock instead. If ads are the original sin of the web, Brave is not leading us to terra nova.

Dishonesty. With its nonsense about privacy and authenticity and integrity, Brave is holding out its ad system as some great ethical leap forward. It’s not.

For publishers, it’s the same old shakedown—nice website you’ve got there, shame if something happened to its revenue—but run by Brave instead of Google or Facebook. Brave will only distribute your

“fair share” if you capitulate to their terms. One of which is that you have no say in whether the share is actually fair.For users, Brave is still going to collect data about you. As Brave puts it,

“When you join Brave Rewards, your browser will automatically start tallying … the attention you spend on sites you visit.” Brave will then feed this data to their“ad matching” algorithm to target you with ads. Oh, sorry—in Brave’s ad marketplace,“users become partners instead of targets”, so I guess they’ll“partner” you with ads. Feel better?By the way, Brave says its

“ads ... do not collect information about you”. But obviously, Brave itself still does—they explicitly say so—because it’s essential to their“ad matching” algorithm. Advertisers, in turn, buy access to this algorithmic targeting. Thus, advertisers may not have the data, but they get the benefits of the data.This shell game around privacy is a recurring theme. For example, Brave boasts that the ad matching

“happens directly on your device” and that they don’t upload your personal data to the cloud. Well, right—they don’t need to, because you’ve already done them the huge favor of installing their browser, thereby making it easy to feed at the trough of your personal data. Moreover, this“local storage” wrinkle doesn’t take Brave out of the business of collecting, storing, and profiting from personal data (which is, in fact, their entire pitch to advertisers). Just the uploading of it. If targeted web advertising is a shit sandwich, then Brave is merely cutting off the crusts.Even then, Brave’s pledge not to upload personal data comes with a huge caveat: they still report

“event activity”—aka analytics—to advertisers. This necessarily involves transmitting information from browsers back to Brave central command. Though Brave claims they transfer data without“exposing or identifying the user”, good luck figuring out what exactly that means.Another example: to redeem Brave’s cryptocurrency for cash, Brave requires users to create a digital wallet with a company called Uphold. Uphold, in turn, requires a pile of valuable information—birthdate, home address, photo ID, etc. Thus, Brave keeps itself smelling sweet on privacy partly by offloading the more noxious aspects to a third party. But ultimately, getting the full value out of Brave still means sacrificing a lot of privacy.

Freeloading. One of the sneakiest aspects of Brave is the implied connection between generating cryptocurrency while browsing and paying out that currency later. It sounds like web users are paying for what they read. In some cases, they might.

But that’s not guaranteed. By substituting its own ads, Brave is also severing the connection between where the ads are seen and who gets the money for those ads. Brave converts the web into a clean substrate for delivering its own ads, without guaranteeing any payment to any publisher.

For instance, suppose a Brave user spends 99 hours on Terrific.com and 1 hour on Shady.com. As I understand it, the Brave gilt generated during those sessions is distributed pro rata, but only if a) the user has opted into Brave ads (thereby generating crypto coins), b) both Terrific.com and Shady.com have registered with Brave as

“content creators”, and c) the user has not chosen a different distribution scheme.Like what? The user can instead decide for themselves who gets the money from those sessions. For instance, they could pledge 100% of it to Shady.com, where they spend almost no time, and none to Terrific.com, the site that morally earned it. Or if there’s actually a liquid market for Brave’s cryptocurrency, the user could just pocket the cash value. In that case, Brave just becomes a cash transfer from advertisers to users, accomplished while standing on the backs of publishers.

In sum, Brave is exploiting publishers to make its ads and cryptocurrency valuable, and demolishing those publishers’ own advertising, while making no reciprocal commitment to keeping those publishers solvent.

What’s the alternative? Brave could’ve chosen to retain some percentage of the crypto-coin wealth generated by their users—like a tax—and redistributed it to publishers. But they didn’t. They could’ve chosen to issue cash distributions to publishers who didn’t want to participate as registered creators. But they didn’t do that either. Brave’s loyalty lies with users. Fair enough. But the lopsided asymmetry of the system is revealing.

Worse, signing up as a Brave

“content creator” is not the end of the struggle, but merely the beginning. In the bad old days, you had to lure people onto your website. But once you did, at least you had a shot at showing them a few ads. Under Brave’s system, you still have to lure them onto your website, but then also make sure you compete effectively against other Brave content creators to preserve that“fair share” you keep hearing about.More broadly, it’s easy to foresee that a system where users control distribution of crypto coins will suffer from forms of systemwide cheating that have nothing to do with content creation. Brave’s creator economy is likely to descend into anarchic corruption in about five seconds. The ethical creators will start to disappear from the system as they find themselves even more underpaid than before. After that, the usual race to the bottom will ensue.

As an economic matter, Brave will fail, because there’s no way for it to succeed. Web ads are a rotten business—a form of regressive taxation upon the web’s least sophisticated users that depends on escalating levels of surveillance to sustain any value. Brave is panning for gold in a river of sewage.

As a web user and programmer myself—not in Mr. Eich’s league, but I muddle through—I no longer think that any level of ad targeting is compatible with a meaningful definition of privacy. Two problems:

Financial incentives create a conflict of interest. The moment you feed personal data into an ad-targeting algorithm, and sell access to that algorithm, you create a conflict of interest. On one side, the user, who wants to protect their privacy; on the other, the advertiser, who wants to pay to invade it. If you’re serious about privacy, the only coherent way to resolve this conflict is to eliminate the advertiser. Rearranging the technological pieces on the board—as Brave does—may look prettier. But it can’t cure the conflict.

These are not your grandma’s algorithms. The idea that minimizing the data going into the algorithm somehow protects privacy is contradicted by what we know about today’s AI and machine-learning algorithms, which are designed to make inferences about what’s missing.

For instance, the EFF has found that even if you block data trackers,

“fingerprinting” algorithms can still deduce your identity from seemingly generic clues left by your browser. And a recent informal test of Amazon’s Rekognition software showed that it could identify a human face with certainty from a blurry 20 × 26 pixel security-camera image.These are just examples. I have no idea how Brave’s ad-matching algorithm actually works. But in general, when a company says it will apply

“machine learning” to our personal data—as Brave explicitly does—we should take it as a promise to infer details that we might not even know were detectable. Again, if you want to optimize for privacy, there’s only one reliable solution: don’t feed personal data to the algorithm at all.“But there’s no way for Brave’s algorithm to make inferences, because it can only access a user’s local data.” Oh really? Speaking as the world’s worst AI programmer, here’s how I would circumvent this problem. I’d buy a giant pile of personal data collected from other sources—oh yeah, it’s out there—and pack it into each copy of my software. Then, when I examine a certain user’s local data, I can still make inferences about that user in a wider statistical context.For instance, the purchased data might allow me to learn that people who visit both Terrific.com and Shady.com are 10× more likely to own a pug. So when I see Terrific.com and Shady.com in a certain user’s browser history—bingo! Serve that ad for

puglovers.net! Best of all, I can still truthfully claim that I don’t aggregate data from my users. Again, I have no idea if Brave does this. Point is—the“local” restriction doesn’t necessarily seem like an obstacle.

By the way, I don’t say this as a privacy optimizer or absolutist. Like most, I sacrifice slices of privacy all the time to get inane web goodies for free. My point is just that a privacy-respecting ad-targeting system strikes me as a contradiction in terms. Though for the same reason, the idea that it could exist is great marketing, like

It would’ve been possible, for instance, for Brave to build the same browser without the ads or ad targeting. Of course, in that case, they would’ve had to charge users. But they didn’t want to. Or more precisely, as a rational economic actor, they must’ve found that advertisers were willing to pay more for user privacy than the users themselves.

Hence the irony. Though Brave presents itself as a browser maker, its business model most strongly resembles that of an ordinary ad-based web publisher: selling user attention to advertisers. Like many ostensible tech disrupters, Brave seems to misunderstand why the current equilibrium exists. Personal data is hugely valuable to advertisers. Brave will likely discover that their minimal-data-upload policy will reduce the price of their ads, which means—yep, pushing a lot more ads. In turn, users will complain, demanding fewer ads, which means—yep, providing more personal data. A vicious circle? Welcome to the jungle, Brave.

Beyond that, the fact that Brendan Eich has done a lot of good for the web, especially at Mozilla, makes the existence of Brave all the more inexplicable and dispiriting.

You know what would’ve been brave, Mr. Eich? Charging users for your software—on the idea that personal privacy is worth it—and puncturing the myth that web browsers must be free. Or helping publishers find a way to induce more readers to pay for the material they find valuable, without the unnecessary indirection of ads and cryptocurrency. Like I do.

Butterick Braverick™

12–17 December 2019

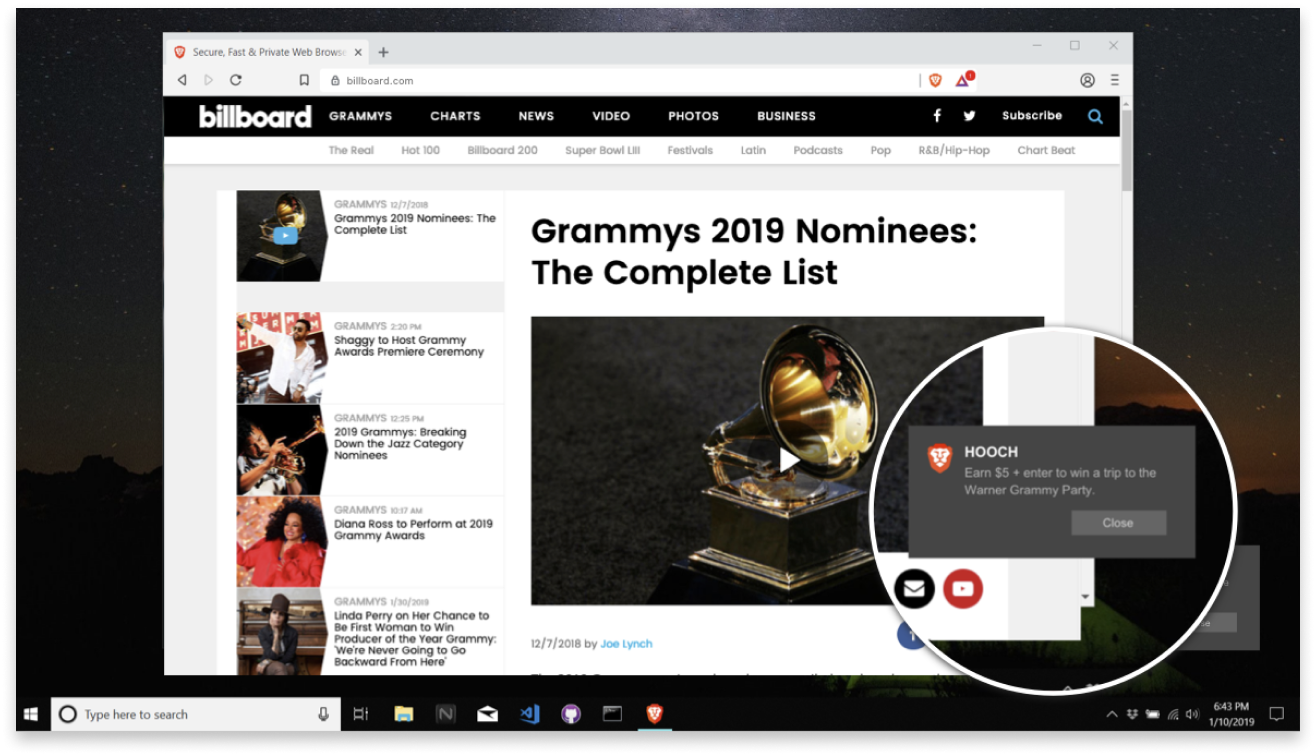

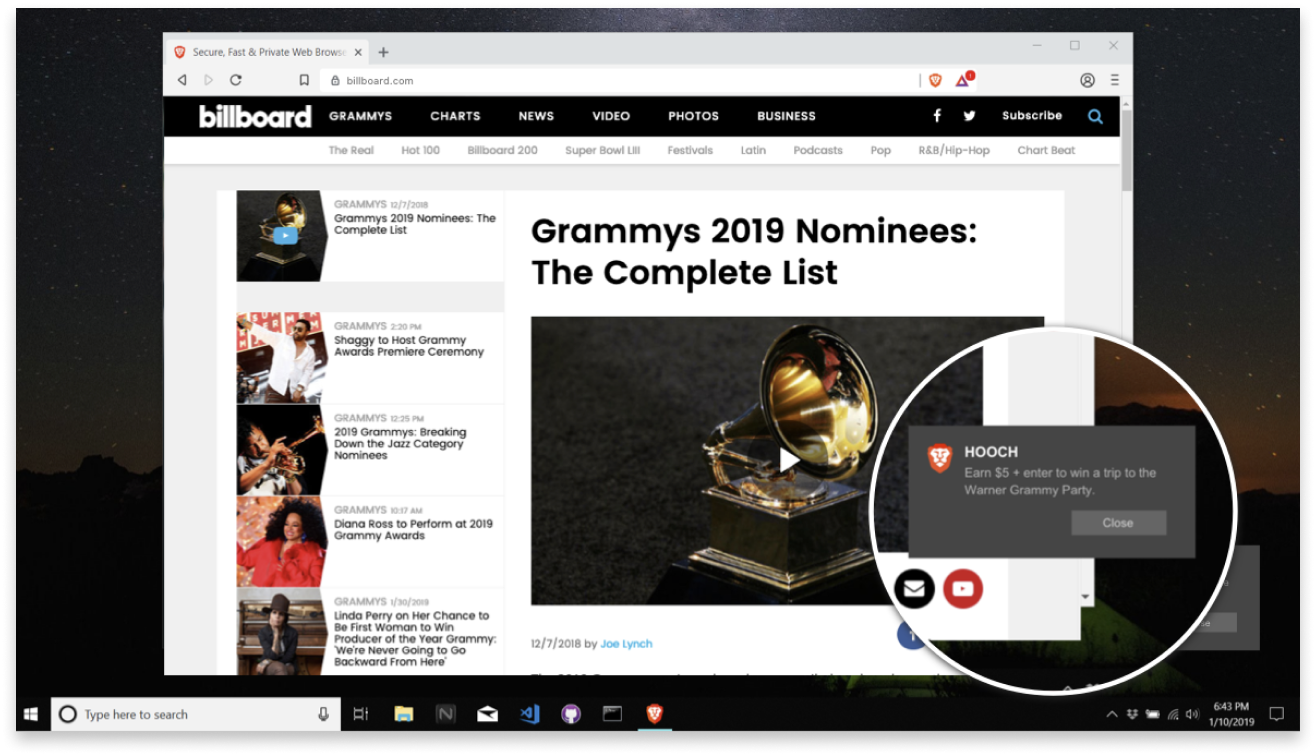

“But as a user, participating in Brave’s ad model is entirely voluntary.” For now. As the weakness of Brave’s revenue model reveals itself, we can expect that the Brave browser will make it tougher to avoid the ads. But even today, you can’t pay creators through Brave unless you’re generating Basic Attention Tokens by watching ads. (In principle, one can exchange cash for these crypto coins, but to do so, you need a digital wallet through Uphold, which costs you privacy.) In any case, if you don’t care about paying creators, and just want to block ads, there’s no reason to use Brave at all.“Why do you care if Brave shows people ads while they visit your ad-free sites?” For the same reason I don’t like any of the effluent flows: they send me useless traffic that costs me real money. But hey, that’s the web—I accept that certain sites exist to exploit people with skills and credibility. Brave, by contrast, is holding itself out as an enlightened company friendly to web publishers, but without actually making any concrete commitments.How exactly does Brave deliver its ads? They don’t literally inject banner ads into the browser viewport, but rather send OS-level notifications with ad links in them. Why anyone thinks this is an improvement, I have no idea. But it doesn’t change the essential point: by whatever mechanism, Brave will display ads to users as they’re visiting my site that I, the publisher, never wanted to appear.

Because of this wrinkle, some have quibbled with my initial use of the phrase

“layering ads over my ad-free website”. This is hairsplitting. Suppose a reader is visiting my site with Brave, and Brave happens to choose that moment to push one of their“private ads” as an OS notification. This notification will in fact“layer over” the screen in some way. Don’t take my word for it—that’s exactly how Brave depicts it today:

When this happens, the reader is naturally going to think there’s a causal connection between the two things the Brave browser is doing: showing a page and serving an ad. Since you’ve gotten to the endnotes of a nerdy tech essay, I understand that you might be the rare person who would infer otherwise. I’m talking about the remaining 99.99% of web users. They won’t.

In December 2018, YouTuber Tom Scott critiqued Brave for its aggressive marketing. He also questioned whether Brave’s escrow policy for unregistered publishers complied with the GDPR. Brave made some changes in response. But the coercive approach continues.

Brendan Eich responded to this piece. For what it’s worth, Mr. Eich, I looked into your product only because a number of readers had asked if I would enroll in Brave’s creator program. What I know about Brave came mostly from reading your website and trying out your browser. But Brave is cagey about many details of its system, and contradictory about others. So you didn’t win me over. But fortunately, no one cares what I think. My best wishes to you, esteemed engineer.